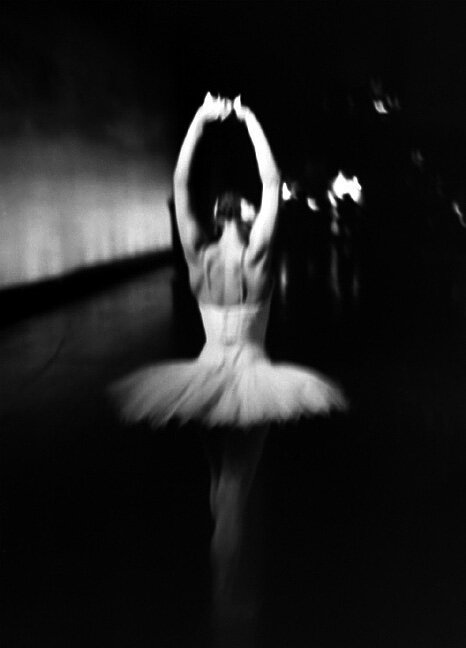

John Goodman, Selections from the Ballerinas portfolio, 2004, Silver prints, 20 x 24 inches

Featured Artist: John Goodman

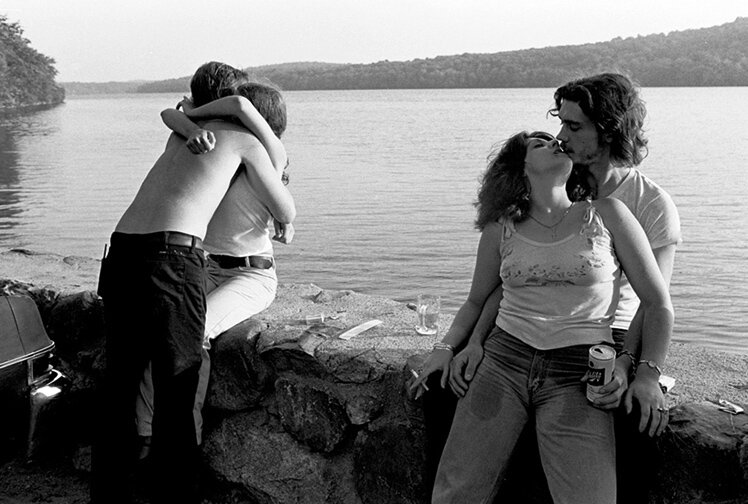

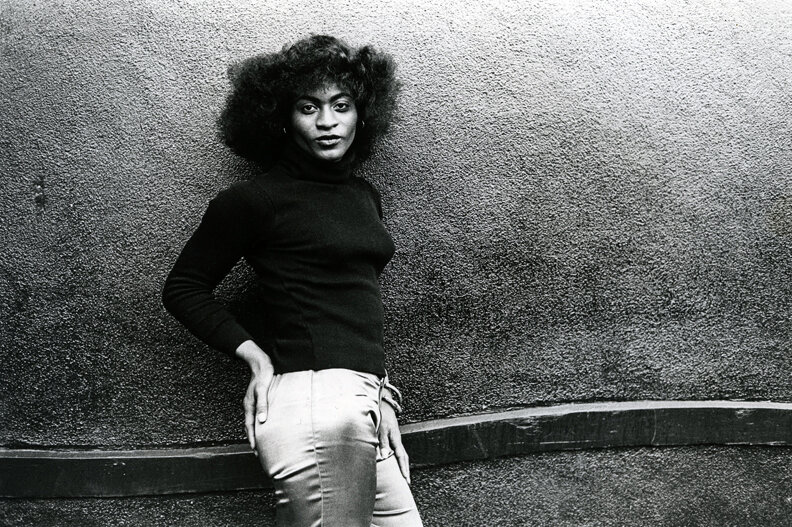

John Goodman, Selections from the not recent color exhibition and portfolio, 1973-1985, Ink jet prints, 24 x 20 inches

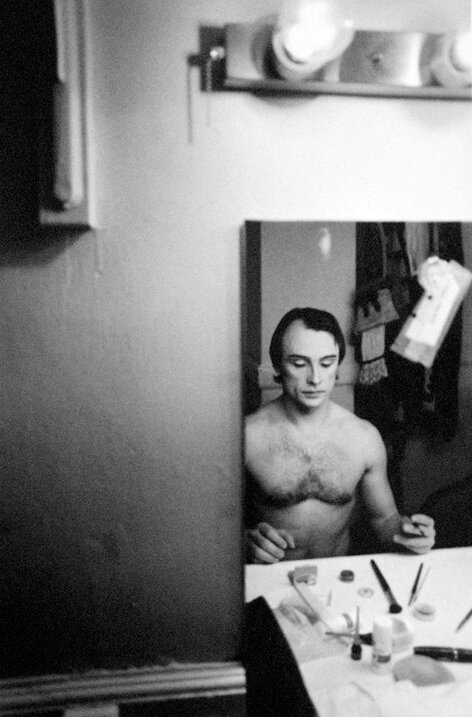

John Goodman, Self Portrait, 2021, Silver print, 4 x 5 inches

I am drawn to the human body and its contradictions, I explore the contest between light and dark, grit and tenderness, power and grace. - John Goodman

John Goodman, Selections from the Havana portfolio, 2000, Silver prints, 24 x 20 inches

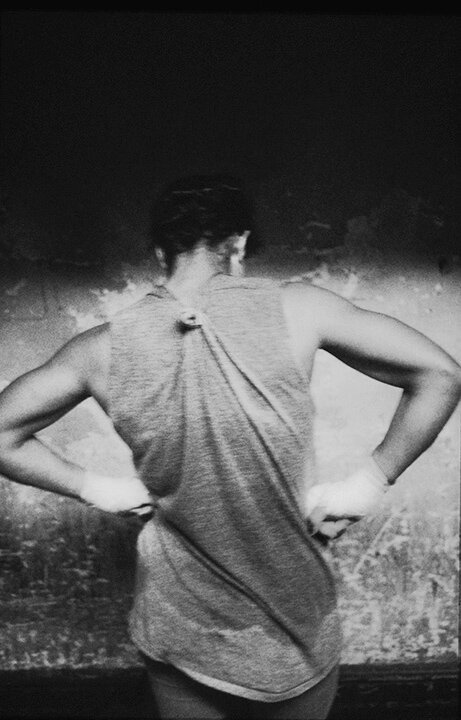

John Goodman, Selections from the Moving Pictures portfolio, 1991-2007, Silver prints, 24 x 20 inches

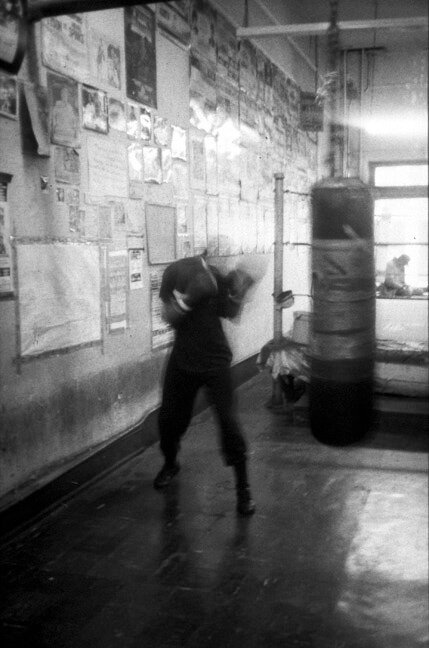

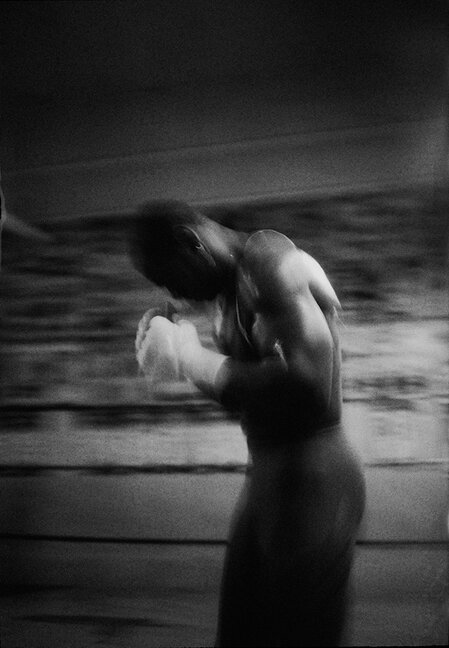

John Goodman, Selections from the Time Square Gym portfolio, 1993, Silver prints, 24 x 20 inches

A conversation with John Goodman

by Jan Pieter van voorst van beest

The first time I got a close look at John Goodman’s work was in 2014 when the PhoPa gallery in Portland featured him in a one man show. The exhibit was titled Black White+Blue and was a great show. I had seen his work before but never “live” which is a shame because John had been around for a long time and his work had been exhibited all over the place. His work is in the collections of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Metropolitan Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and others. As a matter of fact he had several exhibits in Maine before the exhibit at PhoPa (2012, at the University of Maine Museum of Art, 2014: The Caldbeck Gallery in Rockland). He has also been teaching at the Maine Media Workshops in Rockport for a long time.

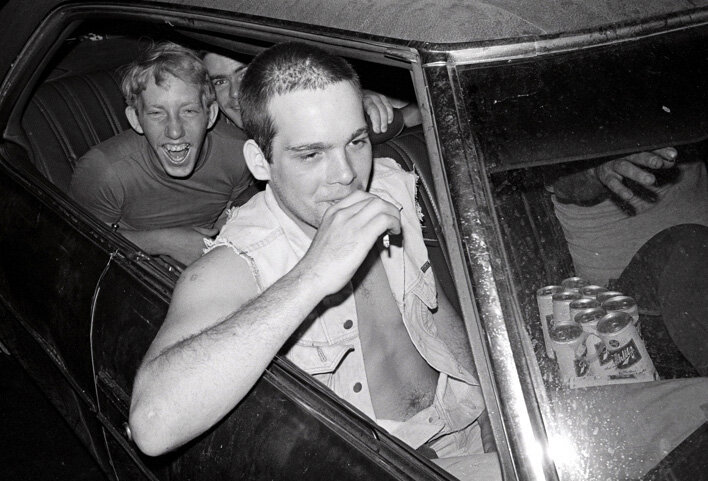

What is more important, Goodman has been making extraordinary photographs for almost 50 years! He has photographed luminaries like Mohammad Ali, Conan O’Brien, Ben Kingsley and many others and then there is the work from the very beginning of his career. He’s famous for the Combat Zone photographs in Boston (raw unforgiving street work but full of grace), for the color photographs he took mostly in the seventies and eighties, and the gritty images of the boxers in the Time Square Gym, and finally, the Ballerina series—always displaying the human condition. It is great to finally catch up with John this month and have a conversation with him about photography, his work and his career. JPvVvB

Jan Pieter: John, you studied under Minor White as a young photographer. White’s work is very different from yours, more in an abstract and modernist tradition and known for his precise printing. So it is interesting to learn what drove you into the direction of a gritty street photography style that you adopted during your career? In what aspects of your work and how, did he influence you? What other photographers influence your work as well- How did it all start?

John: I spent 9 months in a workshop led by Minor White in the early 1970’s. Minor taught me how to see and soon thereafter I found my subject matter on the streets of Boston. The streets were exploding with energy and I was young, impulsive and eager to find my way. I also was intrigued by the rawness of Robert Frank’s Americans and stunned by the story telling by Duane Michals. Minor could not be any more different from these two, but he was a visionary teacher from whom I learned so much. It is interesting to note that Minor is currently, in 2021, having an exhibition of street photography, shot from 1948 to 1953 in San Francisco. These pictures essentially were made before Minor became Minor, when he was finding his way.

Jan Pieter: Having done this for a long time, you must have accumulated a large body of work? What made you decided to print the color work that you shot in the seventies- at a much later time? What made you go back through your files to find “new” material and finally print it after all those years?

John: I discovered the Kodak chrome slides during a studio move in 2006. When I made the pictures in 1973-87 I was intrigued by how the color could play in the street work. The problem was that I did not print color and that I felt that I was giving up too much in terms of image ownership unless I made the prints myself. I also did not have any gallery representation and I had no way to get my work out there. I just took the pictures and put them away. I decided during the studio move that I would take whatever time it took to go through all that I had aimed my camera at over the years. If I just packed it up in boxes and send them into storage I would never see the work. The edit was both frustrating and euphoric but in the end I had a clearer understanding of what I had done and who I was as a photographer. My “not recent color” solo exhibition at the Addison Gallery of American Art in 2019 is one of the things that came from this moment of reflection.

Jan Pieter: At the Maine Workshops, in one of your classes, you spoke to your students about the importance of editing and sequencing. Can you tell us how these are important in your own work?

John: Editing is so important. It’s kind of a life or death thing in that when you determine an image is an out-take, you put it away and in the process you might be burying your real self. Images not chosen just somehow disappear and are no longer part of your conversation. Photographers learn by looking at their work, recognizing when things seem to repeat and re-occur. We shoot impulsively and then we need to understand why we made that image and why it looks like so many other images that we have made in the past. It can take time to catch up to yourself and begin to understand what you intuitively just did.

Jan Pieter: The decision to combine the images of the boxers of the Time Square Gym and the photographs of the Ballerinas series (which were shot ten years later) in one exhibit was genius. It shows a narrative that runs through the whole body of your work. There are many similarities between the two series but they are also different. Can you tell us what, in your mind, tied the two series together?

John: The boxers and ballerinas really have a lot in common. They were pieces of the same puzzle and fit together perfectly. The ballerinas were strong, committed warriors, relentless in dealing with all kinds of injuries but always pushing through every day, trying to perfect their craft. The boxers were essentially doing the same thing, training every day, bobbing and weaving, working to get to the next level. There is a solitude, a oneness that boxers and ballerinas share with photographers. You are out there in the world solo. Every day the boxers train, the ballerinas dance and photographers search and find their next image. It takes a never ending commitment.

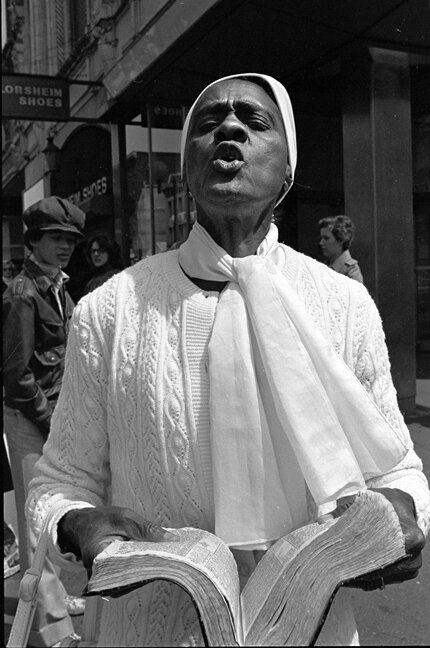

Jan Pieter: You have created a lot of work that would be classified as street photography (In the tradition of Klein and Winogrand). Some of the work was shot under conditions where subjects expected to be photographed (musical events, the gym, the dancers), places where people are quick to except the photographers presence. Many of your images however seem to have been taken on the street of subjects that might not have been aware that they were being photographed. Do you find that this kind of street photography is harder to do today and what would you tell your students wishing to do “street photography”? (In Hungary a law was passed in 2014, making it necessary for a photographer to get permission of all the people that are included in an image taken in public!).

John: Street photography in 2021 is an endangered species. There was a time when it was O.K. to photograph people in the street. If you were on the street you were considered to be in a public space and anyone in a public space could be legally photographed. However the reality is people don’t want to be photographed. Our world has changed and taking those kind of pictures can be considered a violation of someone’s personal space. A colleague of mine has been attacked by people he has photographed on the street. People just want to walk down the street, go about their business and not be violated by “picture” taking. There are pictures that I have made in the past that I probably would not take today.” Woman Driver/ South Boston, July 1977” might very well be one of them. The woman with curlers was stopped at a red light. We saw each other and as I approached with my camera in hand she seemed to somewhat reluctantly give me permission. I then made the picture, the light changed to green and she drove off. I might not have made that picture today.

Jan Pieter: John, your website is split into several groupings of your work. There is your personal work and there are some commissioned groupings as well. Browsing through the commissioned work and the editorial section, I recognize many touches of the street work. There is one wonderful shot of a couple embracing in a museum in front of a Renoir painting which also depicts a couple embracing. Then, on the left of the picture is a shadowy figure exiting the frame. Some might wonder what the shadow is doing there. I think it becomes an essential part of the photograph, giving it that gritty spontaneous street photography feel. So can you tell us where the approaches to your personal work and your editorial work meet? Do they sometimes blend together?

John: My personal and my editorial work come from a very similar place and blend together. My task is always first and foremost to make my pictures and respect the medium. I do not become a different photographer because I have an assignment. Good editors are looking for real work and know how to match up each photographer with an assignment to that effect. All the work I have done my entire career comes from my search to find myself in all my images and to connect to the subject. The couple kissing in front of the Renoir painting, shot at the MFA/Boson has a narrative beyond just the kiss. The blurred figure to the left is added to extend the story and as you said bring some of the street work inside the museum. Photographs that are quickly understood usually have a limited shelf life. Ambiguity adds another dimension and keeps the conversation going. What I love about making editorial portraits is how immediate everything is and how you have to think on your feet and trust your instincts. You walk into a space you have never been in before, to meet a person you have never seen before, knowing that you will be walking out of this space in 30 minutes or one hour or 5 minutes later depending on everyone’s schedules. There is tremendous pressure to perform along with a tremendous amount of creative freedom to do to whatever it is you need to do. I had a close working relationship with Ronn Campisi, the design director of the Boston Globe Magazine when I was starting in the early 1980’s. Magazines were thriving then and they were a vital part of photography as an art form came together to create a fertile and vibrant time for magazines and a real opportunity for photographers.

Jan Pieter: What is next? Are you currently working on any new projects and can we look forward to any new exhibits or books?

John: I am working on a book that ties all my projects together from The Early Street Work, the not recent color, the Times Square gym, Boston Ballet, Moving Pictures, Havana, Identity, along with the editorial portraits and fashion. I am also looking forward to getting back into the world, post Covid. In terms of a new project I am taken by the majesty and grace of trees. We’ll see what happens.

John Goodman, Selections from the Early Work portfolio, 1976-1980, Silver prints, 20 x 24 inches